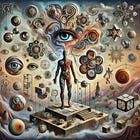

The nature of our mind's "I" is a delightful example of illusory control. We possess it when we wake up, lose it when we go to sleep, and rarely consider the variations that reside between those two states. We hardly ever need to. Contemplation of our conscious lives is left to the supposed fanciful depths of philosophical analysis and is a point of acceptable ignorance for most of therapeutic psychology. Only when things "go wrong" when our thoughts become delusions, do questions of just what our mind is and how it operates come to the surface. It is much like how we go about our lives, blissfully ignorant of what occurs around us until that fateful moment when we stub a toe or are struck by an object we swear appeared out of nowhere.

Thankfully we are not just our mental lives, we have bodies as well. More accurately, we each are a mind that resides and expresses itself within and through a body. The very nature of how our minds construct our perception of the world is through the mechanisms of the body. That natural, mechanistic, and purely material process brings along for the ride of life a quality of change centered on the principle: "Identify that which is different." This principle is a guide, providing us the great power of adaptability to the flux and flow of reality and offering a means of differentiating that which supports or undermines our perception of reality.

"We learn that we are separate beings in the world, distinct from what is other than ourselves, by coming up against obstacles to the fulfillment of our intentions—that is, by running into opposition to the implementation of our will. When certain aspects of our experience fail to submit to our wishes, when they are on the contrary unyielding and even hostile to our interests, it then becomes clear to us that they are not parts of ourselves. We recognize that they are not under our direct and immediate control; instead, it becomes apparent that they are independent of us (Frankfurt, 2006)."

The Body and Memory

While the existence of a world beyond our own body is the basis of recognizing there are immutable facts about the world, facts that do not change however much we will it otherwise, this bodily experience runs headlong into our mind's ability to form perceptions through data selection.

Go down memory lane. It helps if there are physical pictures available, and you'll quickly notice in the pictures that the body now moving about is quite different than that which came out at birth and developed as a child. Now, notice the differences between memory and photos, where in memory there is never a reflection upon that different body, the perspective is always projected outward where your body doesn't reside. Our sense of identity gets its feeling of continuity precisely because the quality of change, pervasive throughout our lives, is not selected for when considering the memories of our lives.

In fact, an active consideration of the body is rarely selected for contemplation during the vast majority of our experiences. We only take notice of it when passing a mirror, come into contact with another object or are otherwise forced to consider our appearance because of social mores like "what should I wear to this interview." The same can be said of a great many other things in our lives, they come to the fore of our conscious consideration only when having jarred our otherwise smooth journey from moment to moment.

This lack of neutrality about the world points to how we are actively engaged within it. We do not operate from a wholly separate place. We are embedded in the world, its objects providing structure for our actions and as focus for the creation of meaning and purpose. This is accomplished by the selectivity with which we conduct our lives and out of which we form our beliefs. We actively promote behavior that encourages the continued acceptance of our beliefs and dismiss or otherwise disregard behavior that does the opposite, whether that behavior belongs to ourselves or those around us.

The Nature of Delusions

It is this active selection that brings us to the nature of delusions:

"A delusion is a belief held by an individual or group that is demonstrably false, patently untrue, impossible, fanciful, or self-deceptive. A person with delusions, however, often has complete certainty and conviction about their delusory beliefs. They resist arguments and evidence that they are wrong" (Psychology Today)

Before going further, here's an overview of the standard types of delusions (also from Psychology Today):

Erotomanic - a belief that someone, often famous, is in love with them

Grandiose - a belief that one is special or possesses special abilities

Jealous - strong belief that a partner is unfaithful or has cheated

Persecutory - belief that someone or group is conspiring against

Somatic - a belief that some portion or entirety of one's body is strange or not functioning properly

These types all share the careful selection of information to fit and/or support the continued belief. Further, as the definition above notes, the person has "complete certainty and conviction" that what they believe is an accurate portrayal of their experience. Indeed, it is that very careful selection of information that allows the depth and certainty of the belief to continue.

Looking at the types and considering one's personal history, it shouldn't take much time to find examples, albeit of a much smaller degree. Believing that one is capable of something others know is patently impossible. Being convinced that one's partner is unfaithful or someone is out to get you. These happen to all of us at different times in our lives and lead to varying degrees of personal disruption. As noted above in our exploration of personal experience, it is filled with gaps of information we rarely desire to fill in unless pushed to do so. Therefore, it is safe to say that, contrary to the opinion that those suffering from delusions are somehow different from or outside the norm of humanity, the process that gives rise to their beliefs is fundamentally no different than everyone else.

Pathology of Delusion

What characterizes the difference between the pathological identification of a delusion and standard beliefs are two qualities:

The degree to which a person resists arguments and evidence.

The harm to self and/or others that the belief directly results in.

Unfortunately, these two qualities are not objectively simple for those desiring an easy answer to the nature of pathology. This lack of clear lines leads to declarations of delusion being used as condemnation or pejoratively when faced with someone with whom there is disagreement.

However, mere resistance to argumentation does not mean the person is delusional unless the conclusion to be reached is that we all are. Evidence does not exist without an ideological structure to explore it and count it as evidence for or against a particular proposition or belief.

Harm, outside the obvious of death and dismemberment, is frightfully difficult to clearly demonstrate and often has as much to do with what is considered contrary to the status quo as a nuanced consideration of the person's wellness.

Thus it is that we come back to the beginning, to the nature of our mind's "I" and the body within and through which it relates within and to the world. There are very real harmful beliefs that can be called delusional. The identification of them and interventions created to curtail their destructiveness should be pursued vigorously but done so with the humble understanding that the delusions do not separate those who have them from the rest of us. In fact, their existence should be a constant reminder that our minds operate in much the same way, and the distance between normality and pathology is in no small part a matter of perceptual degree.

References and Further Reading:

Farnham, Adrian. (2015, June). The Psychology of Delusions. Psychology Today.

Frankfurt, H. G. (2006). On truth (2nd ed.). New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (2004-07-31). The World of Perception (p. 63). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.