Humanity’s Values is a reader-supported publication. Please consider subscribing as a way of supporting the delivery of the content you’re appreciating. Also, feel free to share and expand the community of reflective critcism.

Our shared humanity means we experience a great many things similarly, despite our avowed dedication to the belief in our uniqueness. Despite the modern obsession with individual identity, and the ego-driven desire to make “lived experience,” itself based on a delusion of one’s uniqueness and displacement from humanity, it is our similarities that drive us to bond, suffer, and gasp in relief at even the merest semblence of communal connection online. We strive for such connection to mitigate our disconnection from nature and the fruit of our labors as everything becomes digitized. We pursue these bonds, just as often, to avoid the crushing weight of how often our ignorance would shine were we to stop for a moment and critically reflect.

Avoiding ignorance is parallel to avoiding failure, an inevitable outcome of hubris, cognitive heuristics or bias, and our predilection for always wanting to feel like we’re right. Concerning success, the nature of it shifts based on what one determines is indeed as an achievement, just as to fail is contingent upon one’s identification with not reaching a predetermined goal. In both situations, there is a connection being made between the projected mental image of what we desire and the extent to which it matches with reality. This is why it’s generally so easy to reshape our histories to remember being more right than wrong, for even in the worst case of being wrong there will be some aspect of reality to latch onto as being similar to our desired image. Confirmation bias (seeing only that which agrees with us) isn’t just a present tendency, it’s a fundamental aspect of our continued recreated memory and therefore our sense of self.

Finding Safety in Failure

Safe to say, patients or clients (word usage dependent on one’s focus on providing medicine or a service) aren’t in the counseling office because their lives are grand displays of their own magnificence. Even the patently narcissistic is sitting across from the professional due to a difficulty in their life, regardless of in that case the difficulty is in fact due to the delusional quality of their grand magnificence. I say this not to poke fun, though maybe a little, but to indicate that all clients will to varying degrees be dealing with a sense of failure.

The particular aspect of their life that has fallen short will differ, but not the feeling and identification with a particular instance of having not succeeded. This is likely the basis for being able to provide a diagnosis in nearly all situations of “Adjustment Disorder.”

As with all psychotherapeutically identified pathologies, Adjustment Disorder is as much in the eye of the beholder as it is an identification of an objective malady. The distress, according to the DSM-5, must be in response to a stressor (which frankly means anything the client experiences as being other than a fulfilled desire), and the distress must be “out of proportion to the severity or intensity of the stressor.” Suffice to say, the person wouldn’t be engaging in a service that is, at best, awkward and still prone to social stigma, as psychotherapy, if they didn’t already think their distress was “out of proportion.” The diagnosis is simply a means of providing a medicalized authority to the client’s self-narrative. Not exactly an auspicious beginning for a relationship that should be a safe space for acknowlediging one’s limitations.

Why limits? Shouldn’t the therapist be providing ‘unconditional positive regard’? The client has suffered through a perceived difficulty and the maladaptive response has lasted long enough to cause difficulties in one or more areas of their life. Given stressors are subjectively identified and narratively bounded, in response to a world that is contantly reminding us that it isn’t here to bow to our desires, learning to fail well should be the cornerstone of therapeutic intervention.

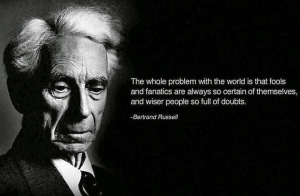

Being Wrong Really Is Ok

Let’s face it, failure (or whatever word one desires to use there) is a fact of life. Being wrong may in fact be far more human than being right, it most certainly takes up a greater amount of our lives. Interestingly, and not without a fair degree of humor, Kathryn Schulz in her book “Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error,” notes that the feeling of being wrong is a lot like the feeling of being right. In being wrong we can quite easily and take a quick self-serving look at it as being right about being wrong. Humor aside, this doesn’t take away from the sometimes brutal reality of having failed.

“The energy, even courage, to rethink a failed piece of work, write, rewrite, inquire, and respond to the comments and questions of a critical reader is crucial for anyone aiming to excel in college."(Leah Blatt Glasser)

Helping clients to “fail well” then is about learning to accept being wrong as simply another aspect of life, one that is as indelible as breathing and Starbucks coffee. The avoidance of being wrong and its consonant feeling of failure is often looked at as something to go to war over, a vicious beast to be slain through structural changes in life or through self-immolation to rise above it like a phoenix. If it is at any time acknowledged and graciously accepted that being wrong does not require destructive judgment, then failing well becomes an easier reality to embrace. Do we chastise the child for coloring outside the lines? Do we look at the scribbled family figures placed on a fridge and condemn the lack of realism? Well, perhaps some do, but their parenting skills are not at all healthy or helpful.

The ability to be wrong and smile is a skill lost as we get older. The reaching for a perfection that doesn’t exist and in practice ends up being a constantly moving goal, is found in the language we often use. From Not One Is Broken, No Not One:

When I, or any of us, approach someone who is suffering, seeing them as whole and complete, strong and resilient, but at the moment blind to this, a person can be seen devoid of our own hopeful projections. Viewing each other as wholes, as complete entities, encourages thoughtful contemplation rather than emotive melodrama. We do not get stuck attempting to fill the gaps or lack, instead noting how much more we are together.

That interpersonal connection is the heart of what I look at as the therapeutic alliance. Failing well is to see life, not as a mechanical object where not fitting means we’re either broken or intrinsically misaligned, but as an organic construction of which we are a part of rather than apart from. Mental life is not then a round peg seeking a round hole, it’s an adaptive organism, with individualized degrees of changeability.

When engaged in any healthy relationship, personal or professional, supportive or therapeutic, teaching and learning how to fail well is not an issue of changing the other, but of shifting the notion of failure as something to learn from and expand through. We can be wrong, even horribly so, without losing sight of and seeking still to pursue doing things differently the next time.