The Comfort of Authority

Why group allegiance often feels safer than independent moral responsibility

The identification and exploration of values is one of the cornerstones of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). In the work that I do with clients, both in therapy and in coaching, this focus on values is often the very first thing we start with. For ACT, values provide a means of giving focus and direction for a person’s behavior, and by extension then will help in the building of goals. Value-directed behavior is the sought-after conclusion for helping in personal development under ACT.

While I don’t disagree with this desired outcome and a person’s personal growth improves as they get clearer with what values their behavior is seeking to support and express, I think what is missing is that behavior was always guided by values, just not always in an actively conscious and deliberate way. Instead of value-directed behavior being a conclusion to reach, it is a reflection to be considered. What exact values were you seeking to support when you did x? Since there’s seldom a situation where only one value exists to be supported, how did they work together to create a narrative web to support the behavior you did?

The answers to these questions, among others, help us acknowledge how nothing we do is contrary to what we care about. Where we go astray is in thinking that we only ever care about just one thing, and that how we go about supporting what matters to us is the definitive and necessarily good way of doing so.

Because here’s the thing about how our mind/brain works: it doesn’t care about truth in anything but a functional way. Truth is a conceptual tool created to justify the actions we have already chosen to do or have done. This does not mean there’s no such thing as truth, just that it isn’t floating around in the air like butterflies that we trap in the nets of our own conscious brilliance.

We Are Wrong All the Time

We are wrong all the time. The only variation in how wrong we are is in degree. History is littered with the detritus of truth claims that ran face-first into the walls of a reality so much bigger than any one, or group, of us can grasp at any given moment. This point really can’t be overstated, and it’s one that people blithely acknowledge without considering that they, too, are just as human as those who believed things that are now “obviously” wrong.

Consider even your individual life if you’re over the age of 5, which I consider anyone reading this to likely be at least that old (apologies to the truly precocious child), and note just how many times you strongly and definitively believed something, only to leave it behind later. From the existence of Santa, to the idea that your parents were infallible, that harm couldn’t happen to you, and that friendships are forever, your life is positively littered with ideas you believed and acted on that have since been shown to be wrong to some degree.

Being Wrong is A Form of Freedom

The thing is, being wrong does not mean you’ve automatically engaged in some gross moral error. The history of the concept of being wrong is unfortunately tied to that of morality, which is unsurprisingly given the bone-deep feeling of wrongness that accompanies the identification of an error, made even more pronounced when someone else points it out to you. Much of the basis of human ethics is built upon an internally felt assessment we interpret through the labels of feelings/emotions, so it is a quick and easy step from being factually wrong to being morally wrong. However…

Far from being a sign of intellectual inferiority, the capacity to err is crucial to human cognition. Far from being a moral flaw, it is inextricable from some of our most humane and honorable qualities: empathy, optimism, imagination, conviction, and courage. And far from being a mark of indifference or intolerance, wrongness is a vital part of how we learn and change. Thanks to error, we can revise our understanding of ourselves and amend our ideas about the world.

Schulz, Kathryn. Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error (p.5)

Schulz’s point here is, I believe, a direct consequence of recognizing values as being supportable by variations of behavior. Consider that the other qualities Schulz points to as qualities are themselves values. We value our capacity for empathy, optimism, and imagination, and applaud the values people hold that guide behavior, like conviction and courage. Digging a little deeper here, we can see that being wrong, our capacity for and inevitability of being such, provides us the cognitive space for all those qualities.

We can be empathetic for the wrong reasons, and empathy can certainly be used for manipulation, as is often the case with charities and political ads. And yet empathy stands as one of the most lauded of personal characteristics.

Imagination, optimism, and courage are quite capable of leading us astray in our actions, often because of some degree of ignorance leading to an inaccurate assessment of our capacity to effect an outcome we desire. And yet, we gravitate towards the optimistic person, cheer on the imagination of artists and creators, and see courage in our heroes, particularly when such has led to their harm or death.

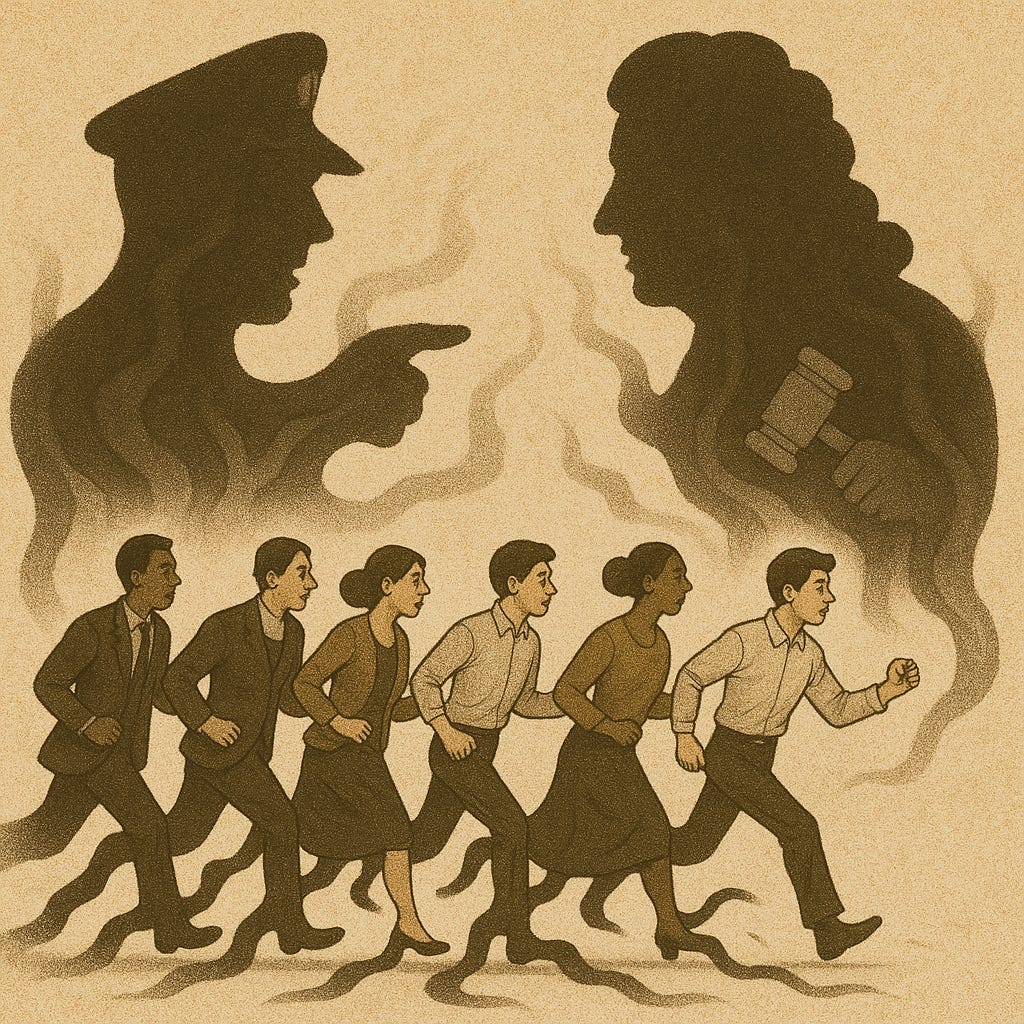

Being Wrong is Made Easier in a Group

To be wrong is not something to be afraid of, and yet we run away from it at virtually every opportunity we can. The oft-used vehicle of escaping from recognizing our limitations is that of a societal structure binding us to a group. It’s really difficult to admit that one is wrong in a group that is saying otherwise or whose identity is tied to a belief/protestation that guides their reason for being. The experimental work by Solomon Asch on conformity points to our soul-deep need for belonging, even if the actions to do so conflict with another form of judgment.

We do not like being alone.

The kind of relatedness to the world may be noble or trivial, but even being related to the basest kind of pattern is immensely preferable to being alone. Religion and nationalism, as well as any custom and any belief however absurd and degrading, if it only connects the individual with others, are refuges from what man most dreads: isolation.

Fromm, Erich. Escape from Freedom (p. 18).

This is why the further we spiral into group-based thinking, and the often maligned form that such takes in identity politics, the easier it is to succumb to the machinations of a populist leader. Once the group is preeminent, the individual is easily dismissed. ‘To make an omelet, you have to break a few eggs’ could be the rallying cry of every political leader who castigates a “them” as justification for removing freedoms even from those cheering the leader on.

The individual is easily sacrificed in the service of the greater group. However, note that the “individual” I’m referring to here is the person in support of the authoritarianism. The power of identity-first thinking is often seen in the creation of an “other,” and yes, that should be a warning, but it’s not the most pernicious quality. Such is actually to be found in the capacity of those to cheer on the fire even as they themselves get burned and call it progress.

The Politics of Being Wrong

“The lesson of Trump’s reelection is that if voters don’t believe his malfeasance will touch them directly, it will remain a low priority for them relative to issues that do, like inflation.

So if Democrats forced a shutdown aimed at producing concessions on civil liberties, my guess is that the public’s patience for it would be short. Americans will support hardball tactics to pressure the president into being less fascist when his fascism starts to oppress them personally, and not a moment sooner.”

Nobody cares about principles much anymore, only direct perceived injustice that personally relates to them and their group. This was the fundamental problem of the Harris campaign. “Democracy” is frankly an easy thing to give up if you think your life is somehow better without it. People give up their power daily for simple conveniences. We are tracked, categorized, and broken down to ad-based identities, and nobody cares because we like Google Maps, want to know how to fit in with others through reviews, and find it easier to belong when doing things that connect us with those supposedly like-minded. Remarkably, we’ve made it as far as we have in the United States without a sociopath in charge, but in the end, the orange idiot is a reflection of our worst tendencies that we’ve been ignoring for too long.

A Return to Character

This is why character, the individual’s focus on ethical living, is such an important part of a healthy society. Note that this does not in any way remove our inevitable capacity for being wrong. Nor does it remove our biological need to belong. What a focus on individual character does is provide a means of balancing or mitigating the effects that tendency and drive have in our lives.

Individual character is fundamentally based on intellectual humility, stemming as it does from the recognition that, as stated at the beginning of this increasingly long article, truth is a conceptual tool to justify our own thinking.

We can strive for greater accuracy in our beliefs; that’s what the broad philosophical discipline of science is concerned with, but greater accuracy doesn’t mean perfect.

Our feelings of being morally right can be seen to point us in the direction of what we care about, our values, without necessarily shouting that every idea we have attached to that value is inevitably good and leads to the outcomes we ideally want.

We can start asking ourselves when the last time we felt comfortable stating a thought that went against a group-held belief, and whether the call for subtlety and nuance is met with dismissal and outrage.

We can make better communities and contribute to a better country, but it starts with the hard work of wrestling with the proclivities of our humanity that undermine the freedoms that come from struggling with being wrong.