Your Beliefs Are Less About Reality and More About Allegiance to a Group

And yes this is a rational thing to do

In what is fast becoming one of my favorite essays, David Pinsof delightfully skewers the notion that the central problem with today’s politics is that people are misinformed. That, if only they could be encouraged, incentivized, and/or cajoled into being rational creatures, they’d all get together in a socialist utopia where the very nature of human beings and the evolutionary history that drove our biological development would suddenly disappear.

You see, it’s not that we’re hierarchical, coalitional, self-deceiving primates—forged in the crucibles of Darwinian natural selection—don’t be so cynical! No, the problem is that other people are biased, ignorant, gullible, weak-willed, and misinformed. They don’t know what’s best for them. They need us to nudge them, raise their consciousness, purge them of misinformation, and teach them who their political enemies are—you know, the people who happen to be our closest rivals in the social hierarchy.

Frankly, I encounter this kind of self-serving Pollyanna thinking quite often in therapy, not just in clients, but amazingly from other mental health therapists who should know better. At least, they’d know better if they spent more time with philosophy and biology texts to question their assumptions about the world. Alas, the draw of being social change agents righteously ushering in a religious revival in the name of post-modernism and the elevation of subjectivism masquerading as “lived experience,” is simply too strong. That this involves weekly, if not more often, meetings to the tune of hundreds if not thousands of dollars (if you’re into psychodynamic psychotherapy) each month, only proves that for all the lamenting about being in the latest iteration of “late stage capitalism,” market forces are well and truly alive and well.

I call it self-serving because every time someone uses the term “logic” or “reason” to critically appraise someone’s lack of this particular quality, it is inevitable that you could substitute “agreement” and nothing would change. In other words, “logic” and “reason” have become the secular equivalent of “true belief” in the religious world. And, just like there’s no such thing as a “true” believer (as in someone who is somehow “pure” in their adherence), only those who espouse allegiance to a group ideological structure, there is also no such thing as a purely logical or rational human being, at least certainly not in the way that is being promoted.

What, exactly, is this “logic” and “reason” that is so often touted by those who think “science is true whether you believe it or not”, amusingly conflating a means of evaluating claims with particular claims themselves? “Reason” here is supposedly that which is opposite of, or at odds with, or divorced from, emotions/feelings. It’s often used by men upset at their spouses, or by men, again, who don’t see why other people don’t agree with them on a topic they’re woefully ignorant of. This isn’t meant to say that women don’t have a similar tendency to think they know more than actually do and prognosticate; such is a seemingly indelible human tendency (one that I’m sure I lapse into at times). The difference is that rhetoric concerning “logic” and “reason” isn’t often used, instead relying on personal or “lived” experience as a just-so epistemic source.

No There Are Not Systems in Your Brain

Unfortunately for everyone who thinks they’ve hit upon a pure source for opinions, there are not, in fact, two different systems making claims, but one system with two elements. First comes emotion, understood as the biological arousal system taking note of something important (known also as ‘salience’), followed by a slower, at least in comparison, appraisal that is concerned with consistent alignment with previous experience, and then we have the conscious expression of this broad process in the form of mental verbiage.

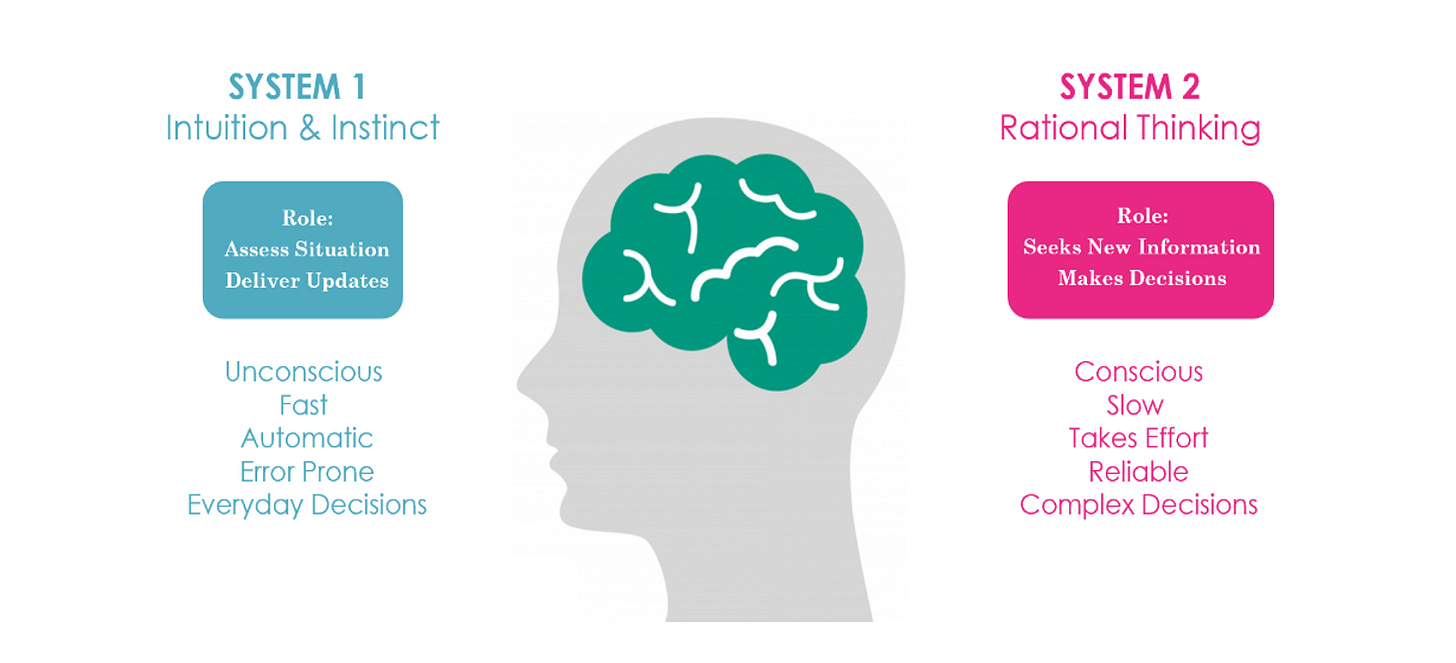

Often therapists or psych professionals who really should know better, start talking "System 1" and "System 2" in the sense of the image below as two separate things; they are not actually understanding Kahneman at all, but are simply perpetuating the non-biological nonsense of emotion being distinct from reason.

It's an unfortunate use of the term "system" when a better framework would be one system, appraisal, that has two general processes within the whole. Much of your "reason" is very much unconscious, since you don't ever choose the thoughts you have, and to call one "slow" is only in comparison to "automatic." What takes effort is not reason, but the social process of criticism and evaluation using various tools.

“System 1 and System 2 are so central to the story I tell in this book that I must make it absolutely clear that they are fictitious characters. Systems 1 and 2 are not systems in the standard sense of entities with interacting aspects or parts. And there is no one part of the brain that either of the systems would call home.” (Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 29).)

So when you engage in thinking, you are emoting just as much as anyone else. You can’t remove the emotional appraisal from your biology. In fact, for fun, consider this question: who chose what to think about? Follow it with: Did you choose from a myriad of potential issues to consider, or did the initial thought come up, and you continued the story? Here’s another question to really get you to doubt being the master of your cognitive domain: To what degree did the environment contribute to what you considered important to think about? And, could I have thought anything I wanted?

The quick answers to those questions are: not you, the latter, everything, and no.

So just what then are our thoughts and the beliefs we conflate with them, really about?

Behavioral Guides

Let’s view cognition through the analogy of baking cookies, with the need for specific ingredients for a particular outcome. For our first ingredient, consider the basic essential biological need of all organisms to direct limited resources towards goals. Now, add being in social environments, whereby those limited resources are organized, provided meaning or importance, and everyone in those environments is jostling for those same limited resources. Lastly, we’re creatures that, like all organisms, take the path of least resistance. As Kahneman puts it:

“A general “law of least effort” applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action. In the economy of action, effort is a cost, and the acquisition of skill is driven by the balance of benefits and costs. Laziness is built deep into our nature.” (Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 35). (Function). Kindle Edition.)

When we want something, there is a context supporting why we want it, and providing the means to get it, albeit to varying degrees of social support or shaming. Beliefs, at the conscious level, here, are shorthand declarations (supported by an enormous amount of unconscious processing) about how that context works and provide the rationalization for why we then behave or engage the way we do.

This is where Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) often shines, being as it is a tool for critical thinking, even as it unfortunately also tends to perpetuate false notions of how reason works. This is also where those lists of so-called “cognitive biases” raise their scary faces, reminding us of all the errors we can make in our opinions. These biases are better understood as heuristics, as self-serving shortcuts when faced with the enormity of the data we’re embedded in as biological creatures. Our brains are far less concerned with grand notions of truth than with reducing errors in judgment to maintain the felt consistency that results from seeing how, when behavior A happens, effect B is achieved. If that means denying data points, conflating others, or making ones up, that’s what it will do.

For all of us faced with the potential shame of being wrong and possessing inherently lazy brains, errors in judgment are inevitable. So what is one to do to curtail access to data that undermines our judgments, and help with that initial biological need we all have to manage limited resources?

Welcome to the second purpose beliefs have: group signaling.

Group Alignment

Ever wonder why a person can say they believe something and yet their behavior doesn’t seem to align with it? Conversations with family about political matters are often an easy source for seeing this, though other sources of examples abound. If you genuinely believe that democratic leadership is behind a global cabal of satanic pedophilic cannibals, as the QAnon adherents do, then it makes sense to fall for things like “pizzagate” and shoot up a restaurant in search of abducted children. Here’s the thing, though, since that incident only involved a couple of people, and there are thousands of QAnon devotees, so why are they all not assaulting Democrat leaders and Hollywood elites? I dare say that a fair number of them still lined up at a movie theater for the latest blockbuster or curled up on a couch for an evening with their streaming service.

The reason why behavior doesn’t match belief? Because these aren’t only beliefs about the world, but also signals of solidarity with others.

Every time a conspiracy theory is uttered, every time a simplistic slogan like “defund the police” is declared on social media without any concern for how that would never actually work or promoting an idea of a group that does the same thing just under a different name, or people declare the evils of capitalism even as they commodify their lives on TikTok, the statements are not really meant as “here is how I see the world” but instead are asking the question: “Who is with me?”

This is where the question of functionality should always come up for us when confronted with any form of behavior, especially when it seems to make no sense. Functionality is essentially the question: what’s the purpose or goal of this? Or, what does the person hope to get out of this? Quite often, the answer to this is belonging.

As Dan Williams notes in his must-read article, “We Are Confused, Maladapted Apes Who Need Enlightenment:”

First, the modern world radicalises our reliance on social learning. When forming beliefs about topics relevant to modern politics, we almost always lack the ability to cross-check what we’re told against our experience, either because it is too distant in space and time or because the topics concern abstract phenomena (GDP, inflation, demographic trends, economic growth, etc.) that no one can directly experience.

Remember, we are biological, socially embedded creatures, and therefore at the mercy of instincts and evolved processes that, while flexible, still answer to that basic resource question: how can I get what I want with the least amount of effort?

Social shunning, or its modern equivalent “cancelling,” is powerful precisely because of the reality that our social-embeddedness is the structure through which resources are allocated. As the old saying goes, “words are cheap.” Yes, they are, and that’s why in a world increasingly centered on the politics of identity, words are an easy, cost-effective way to be in the “right” group.

So the next time you find yourself getting upset about what a person says, and increasingly flabbergasted at how “anybody can believe x nonsense?”, remember the evolved organism that you are and the one in front of you. We’re not at war with our emotions; we’re active participants in an environment we co-developed to meet the needs of evolutionary biology.

Words do matter. Ideas are still important. But what we are as a species never goes away.