We Are Embedded in Reality, Not Creators of It

How perspective blinds us to a world bigger than ourselves

Like most of us, I’m not a fan of events happening that seem to come out of nowhere, particularly when they’re negative or detract from my current goals. Whether it be an event related to work as in a business idea not panning out the way it was hoped, or one’s perception of the likelihood concerning a political outcome doesn’t materialize, or relating to another who has deceived to the point of self-destruction, the internalized question is the same: “Where did that come from?!”

In the situations above, and any other time confusion reigns concerning an unforeseen outcome, hindsight is often varying degrees of annoying. Being human, we forget all the times questions came up and inquiries were made, as well forgetting how often predictions were more accurate than not. Instead, faced with the frustration of the world not operating the way we would like, and not aligned with the manifestation of Values we desire, self-castigation of the form “I should have seen it coming!” is the result.

The therapeutic philosophy I call Relational-ACT has a principle concerning the nature of subjectivity, that such is a perspective rather than a creative enterprise. People often describe their subjective experience as a generative action, as creating reality, and when crossing into some versions of religious ideology (the “name it, claim it” crowd, as well as the entire absurdity behind “The Secret”) promote the idea that we can shape and mold desire into physical manifestation.

The “heal thyself” movement, “positive thinking” self-help moguls, and “prosperity gospel” peddlers are simply larger-than-life advocates of a basic tendency in general human thinking. Our ego, the perspectival “I” at the seeming base of felt experience, is perceived to operate as a creative generator, molding out of the disparate parts of the “external” world a coherent picture. There is a lived-in dualism at work here, such that the internal world of consciousness is acted upon by the external world of objects, with the result being consciousness sees what is supposedly already existent. In other words, we pull from the external world things as they supposedly are, like a puzzle where all the pieces are available for us to simply put together in a pre-established form.

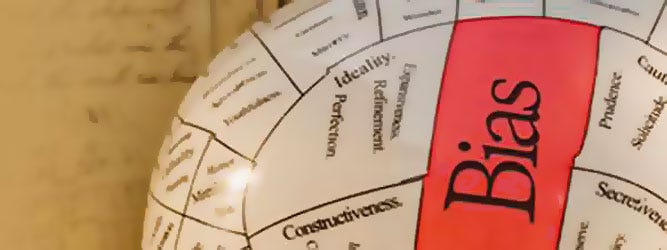

With that intuitive assumption, it becomes easy to see why the “manifesting” gurus promote what they do. If you’re pulling pieces of the real out of reality by the power of your consciousness, then “creating” reality is an easy next step to take. Further, such thinking is at the core of every bias, conspiracy theory, and absolutist epistemology that undergirds dualistic forms of religion and politics. “I just call it like I see it” or getting frustrated by how someone else doesn’t “just see what I see” are declarations of this dualistic manifesting thinking.

The channel of frustration based on this false notion of perception leading to anger and attempts at control through various forms of power, is a slippery one. If the belief “I just see how it is” is, as is inevitable, confronted by competing declarations, themselves based on the same false notion of perception, frustration leads to anger, and anger leads to self-righteousness, the self-serving moral feeling behind every form of authoritarianism.

Perspective is Creatively Embedded

Despite how the feeling of perspective is experienced, like so many things that make an intuitive level of sense, it is not, thankfully, an accurate understanding of what is going on. For two reasons:

The dividing line between “internal” and “external” is superficial and itself simply a perspective device for labeling. They are not separate spaces, entities, or metaphysically of different substances.

Without a clear dividing line, our consciousness occurs within the same reality of which it is manifest from, which means we do not create reality so much as we are already one eruption of it, embedded as we are in a particular form, no different at this level than anything else that exists.

There’s a lot of philosophy going on here, and this is not the place to go into all of it. However, no philosophical pondering is worthwhile unless there’s a pragmatic or functional result. As much as I appreciate a good bout of intellectualization and reflection, the question of “How does this effect my life?” is one I try to keep in mind.

As noted in the “Wiley Handbook of Personal Construct Psychology,” in discussing constructivism:

“With the constructivist the endpoint of all advances in knowledge, whether it is logically reasoned or empirically investigated, is the quest to anticipate and validate. Whether one is discussing the lives of people, the nature of death, or the origin of the universe, the final record ends in a question, not a conclusion.”

Imagine for a moment what it would be like for our conscious experience to actually manifest reality in the sense of pulling things out of it. How would any of us have conversations? How could anybody be certain, as any level of social interplay demands, that what is being said and done is even approximately similar to what is being heard and seen by another? If each person is uniquely relating to reality from their own idiosyncratic lived-experience, there no longer exists a common through-line for social comprehension.

Beginning with the recognition of our physiological embeddedness in reality, we can acknowledge how ignorance is not a moral failing but an inevitable aspect of our thinking process. We simply do not have access to all there is to know, even within the easy reach of our own hands. We deal in a world of varying degrees of certainty. This is not grounds for saying we all possess different realities, it is instead a foundation for noting we all inhabit the same reality, just from different perspectives. We are not the spider spinning a web, we are the nodes of intersecting lines in the web itself. We are not creating situations so much as attempting to make sense of the situation we already find ourselves in.

Witnesses to tragedies can offer widely disparate accounts of what occurred and yet nobody discounts that a shared event happened. Siblings raised in the same home can and often do have wildly different accounts of their parents and yet still recognize that they lived together. This is, I believe, related psychologically, to the Second Law of Behavior Genetics, where it is noted that people raised in the same home are no more similar to each other than equally related people raised apart. The interactions at play here are simply beyond individual conscious comprehension or control.

Human beings are notorious for our tendencies towards confabulation, i.e. distorting memories to suit present desires established through our worldview. None of this is to declare our perspectives being without purpose or effect, they are powerful variables in the construction of relational reality, but they are just that, variables. Remember, we aren’t the spider, we’re embedded in the web already spun by reality.

This embedded principle stems directly from the way our minds function and our bodies operate as interactive vehicles with the world. Daniel Kahneman speaks of “System 1” and “System 2”, knee-jerk automatic responses and deliberated rational considerations respectively, noting that:

"As a way to live your life, however, continuous vigilance is not necessarily good, and it is certainly impractical. Constantly questioning our own thinking would be impossibly tedious, and System 2 is much too slow and inefficient to serve as a substitute for System 1 in making routine decisions. The best we can do is a compromise: learn to recognize situations in which mistakes are likely and try harder to avoid significant mistakes when the stakes are high.” (Kahneman, Daniel (2011-10-25). Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 28). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition.)

Living with Our Mistakes

It is the mistakes to which we now turn. Too often we consider our awareness as a lantern, an all-seeing eye. The negative consequence of this is alluded to in declarations of “he lives in his own head” and “she doesn’t know anything beyond her little world.” When we experience events that hit us “out of left field” or that blindside us, these are examples of cognitive mistakes or bad guesses. Rather than a lantern, our perspective is far more like a flashlight upon the canvas of reality. What lies outside the beam is going to catch us unaware no matter how often we attempt to swing it about, either deliberately or wildly.

The practical advice for life stems from this. If what we refer to as experience is the activity of our lives, itself based on limited perspectives blinding us to what, even in the most generous of appraisals is a vast panoply of interconnected reality, then any time we fall prey to thinking “x is happening only to me” or “y is wholly my fault” or “he only has himself to blame,” we should immediately acknowledge that our judgment is missing a lot of data.

What we are unaware of still happens and has influence. As a simple statement, this appears to belong to base-line common sense. Any honest skeptical appraisal of our opinions however will lead us to acknowledge that much of what we believe is not due to careful deliberation on our part but to varying degrees taken on as matters of acquiescence to some authority, like our parents, friends, teachers, and institutional dogmas. Even the most mindful of us can fall victim to that feeling of certainty leading to a declaration of “such and such must be true.”

Indeed, the more certain we feel, the more likely we can assume how much the multi-headed hydra of cognitive bias is running the show.

As has been noted by many social critics: “Google has made us all experts.” Be certain that the sarcasm is thick in that statement. The mere accrual of information does not absolve the limitations of perspective and awareness as facts do not stand alone. Your lived experience is not a tool leading you towards truth, but a doubling down on the cognitive biases that lead to the sweetest of all all feelings, the feeling of being right. Confirmation bias isn’t a problem of one side or another of any social or political issue, it’s endemic to being human.

If we work at remembering that our perspectives are not in the business of creating reality but of distilling it to fit within our notions of what is right, we will have set foot on a journey of constant discovery, a road of epistemic humility, where we learn to dialogue instead of attempting to enforce acceptance of a limited world.

References:

The Wiley Handbook of Personal Construct Psychology, by David A. Winter & Nick Reed