For most people, the classic assumption is that there can be only one identity, one "I," that moves through events, observing and directing behavior. Personal experience seems to support this notion. Thoughts and emotions seem to arise out of the maelstrom of our internal world in response to information we believe ourselves capable of comprehending. Yet the seeming ease with which this occurs obscures a wider situation. If we switch our perspective to focus on the "one-off" experiences, we'd start looking at ourselves very differently.

What happens when we do things that "aren't the real me?" What are we attempting to say when we respond to someone's opinion of us with: "You don't know the real me"? When confronted with behaviors we'd rather we never have done, the very notion of "doing better" means we have it in us to react in different ways to similar situations, so why did we not do so the first time? These questions and the answers to them are often based on viewing the self as if there is a real version caught behind a cloud or other obscurity.

"The recognition that something phantasmic (projected, imaginary) functions as a façade behind which the real thing might be hidden is implicit in all phenomena of pretense or delusion and it is also taken for granted in the many common, quite casual, expressions that refer to the ‘real’ world, self, or social state of affairs and enjoin us to return to it. Yet the relationship between fantasy and ‘the real’ remains perplexing." (Hurst, 2012)

This facade or image or projection is, so we tell ourselves, not the real me, and yet, where does it come from, and who then is doing the behavior that the facade looks upon? The reality is that while we at times feel distant from what we do and feel disconnected from the perspective-taking experience that we call our self, this has far more to do with a desire to not look at ourselves honestly rather than any actual description of our lives. We are far more than any one action, emotion or thought, any singular framing of image or projection, with the greatest source of our limitation being a tendency to lose sight of this very fact.

Genetics As Destiny, But Not Really

When attempting to explain who we are, inevitably, family is brought up, and, at least to some degree, that means genetics. This gene-centered view of ourselves has been helped along in the last couple of decades with persistent headlines declaring that this or that personality trait, mental illness, or disease has been found to have a genetic link. At an intuitive level, this focus makes sense as genetics is the basis for life, and we all spend time wondering how much of our parents are in us as we develop.

"One thing that early gene-personality work overlooked is that a lot has to happen to allow DNA to code for specific hormones/neuropeptides, that then have to act at the cellular level to subsequently influence personality. In short,genes need to be expressed at a cellular level in order to influence personality, and so one place where a genetic researcher might want to look to examine gene influences on personality is at this expression--that is, what genes are being unzipped by RNA, so that specific hormones/proteins are produced?" (Psychology Today)

Finding a singular gene-trait relationship is far from simple. One way to consider this is from the perspective of our own lives, where a consideration of the influences on our lives exponentially expands with each social circle we expand our vision to. There are our immediate friends and family and co-workers, followed by their friends and family and co-workers, and so on. Imagine each of those individuals being a gene, with varying strengths of relationship to each other person, the resultant entirety being your whole genome. While this image is not meant to convey precisely how genetics works, it does help indicate the complexity involved.

Another way of putting it is from the same article: "...conceiving of genes and personality not as simple one-to-one relationships, but instead, as complex systems of genes that work in concert to express a personality trait." (Psychology Today)

Personhood: The I At the Heart of an Identity

When asked how personality develops, Dan McAdams, professor of psychology at Northwestern University, discussed the potential role that genetics plays in providing aspects of our personality to us, then went on to describe the notion of a life story:

"A person’s life story is an internalized and evolving narrative of the self that reconstructs the past and imagines the future in such a way as to provide life with some sense of meaning and purpose. The story provides a subjective account, told to others and to the self, of how I came to be the person I am becoming." (The Atlantic)

Consider that personality, as much as certain grounds of it may be provided for us by genetics, is the means through which we interact with others and our environment. However, the individualness of who we believe ourselves to be is funneled through the broader social structure or Identity, that we find ourselves wanting to support at any given moment. Think of someone who has a certain brash way of handling difficult or stressful situations. If they’re a parent, such personality will show up in particular actions based on how they want to support that Identity/Role. Also, though, the person has a political Identity, which means some behavior will be selected in other circumstances to support that Identity and bond with others who share it.

This is helpful when accounting for seeming hypocrisy in people and attempting to reconcile how a person can show up one way at a rally for their political leader or online in support of their religious Identity but then treat their friends, family, and coworkers differently. It’s the same person showing up in service of different socially constructed Identities.

Who we are in relation to other people is far from singular; it is a multifaceted evolving process, taking in new information all the time and responding in as consistent a way as possible in support of and solidarity with others who share the same label. Identity, rather than a thing separate from the world, is instead a way for each of us to organize our experiences into a manageable and coherent structure to then experience consistency with who we believe ourselves to be.

Coherence and Consistency in Support of Social Bonds

When discussing the human need for coherence and comprehension of living, Hurst (2012) notes:

"It is most ‘realistic’, or closest to being true to the human condition, to admit a degree of uncertainty or undecidability concerning what happens and admit the possibility that there could be more to events than human cognition can cover."

That uncertainty drives both our continued conscious engagement with an expanding life and the shifting nuance of the various social Identities we seek to reconcile. We want to be prepared for as much as possible, not to be wracked by the winds of fate and chance. We do this by working through the varied perspectives we're connected to, in other words, the people we have relationships with.

"The semblance consists of multi-facetted appropriations of events, which incorporate, not necessarily harmoniously, my singular perspective (personal experience), the shared perspectives of various groups of others (consensual reality), and a phenomenal or objective ‘facticity’, which is intersubjectively shared among most humans because we share certain faculties." (Hurst, 2012)

This "semblance" of Hurst is the approximation of reality that our minds create, essentially a perspective.

Perspective is simply a way of noting we construct our experience from the inside out, from the core of who we believe ourselves to be within the social Identity we are seeking to support. A perspective or opinion is shaped by all the influences (past, present, and considerations of the future) in our lives, as well as the inner sense of ourselves and the demands placed on us by needing to support our social labels/bonds. When sharing our perspective or opinion, we are as much telling someone a story of how we look at ourselves as we are signaling allegiance to those labels/bonds of Identity. The dissonance that I’ve spoken of before that I consider a natural human state is often an experience one has here in juggling that sense of self with the demands of social connections.

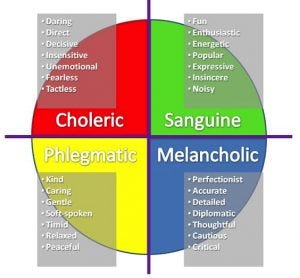

We constantly build a facade or presentation to interact with the world. Rather than stalling at introversion or extraversion, melancholic or choleric, we see how our personalities are responsive within a vast interconnection of social relationships.

Instead of "I'm shy because I'm introverted," it's "I act shy because it slows down the number of interactions I deal with and is how I've learned to work within the world." Instead of "I'm social because I'm extroverted," it's "I engage actively in building social relationships because I've learned to deal with the world through information gathering."

By looking beyond personality labels to how the self exists within a multitude of social bonds, we move past static responses to situations and into dynamic places of potential behavior. Forces like genetics may have set a particular spectrum of possibility for each of us, but within that arch is a virtually unlimited ground for human expression if we but learn and stretch.

References:

Hurst, A. (2012). On the meaning of being real: Fantasy and “the real” in personal identity-formation. South African Journal of Philosophy, 31(2), 278–289. doi:10.1080/02580136.2012.10751775

Kraus, M. W. (2013, July 11). Do genes influence personality? Retrieved June 26, 2016, from Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/under-the-influence/201307/do-genes-influence-personality

Further Reading on Identity:

Eysenck, H. J. (1990). Genetic and environmental contributions to individual differences: The Three Major Dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality, 58(1), 245–261. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00915.ri

Roberts, S. E., & Côté, J. E. (2014). The identity issues inventory: Identity stage resolution in the prolonged transition to adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 21(4), 225–238. doi:10.1007/s10804-014-9194-x