For those philosophically minded, William Ockham will immediately engender various degrees of analytic glee, the name synonymous with logical parsimony or simple explanation. The more user-friendly phrase concerning parsimony is: "Don't multiply entities beyond necessity." Then again, perhaps the phrase isn't as friendly as it may be to some. Thankfully that's rather the point here, simplicity being, like beauty, in the eye of the beholder. Consider a rose possessed of a particular color and a certain number of petals arising out of a stem. To the average person, it is a thing of beauty. To a botanist, there will be an entire history of breeding involved. To a chemist, there will be a litany of compounds and scents included. Which one is more simple? Is that even the right question? For Ockham, the answer to the latter is most certainly not.

A Need to Explain

I was recently reminded of simplicity as being perhaps the most pernicious form of confirmation bias with the performative outrage concerning the opening ceremony of the Olympic games. There’s something inherently irksome about people masquerading as victims while declaring their moral superiority based on a bottomless ignorance of other cultures and history. The first two decades of my life were spent in this virtue-signaling echo chamber of fundamentalist Christianity, constantly on the lookout for things in the world to be upset about, regardless of or even deliberately ignoring context, to find confirmation of the cosmic war between God and Satan, good and evil, the righteous believing minority and the secular Machiavellian powers of the world. It was utterly exhausting living it and continues to be so when simply witnessing it.

The lack of care concerning highly edited photos, contradictory information regarding history and culture, and statements from the art director noting that the manufactured outrage is based on false information are utterly incapable of reducing the simple confirmatory belief that one has been attacked. There are, of course, plenty of examples all over the political map of people responding performatively so as to declare their continued allegiance to a social identity. This simply indicates a human proclivity towards narrative being at the beck and call of reducing uncertainty because one thing is certain: if you’re always right, there’s not much anxiety to be found in a lack of humility-based critical reflection.

The need to offer explanations is not only a seeming necessity but, as can be seen in even the most cursory observation of social media, the source of a great deal of social fracas. Some of the earliest childhood memories are related to giving explanations for behavior in a manner to deflect guilt, as when explaining a broken window or why there's chocolate on fingertips despite being told not to eat dessert before dinner. Such stories certainly continue into adulthood, though the ramifications of our explanations become exponentially more. Issues of social policy will take into account explanations for human behavior, where, for example, the American justice system is predicated on the belief in behavior being based on a uni-causal version of free will. Matters of geopolitics rest on explanations of human interaction, and the role force plays in building and maintaining countries. Environmental concerns run through the sieve of explanations concerning biological diversity and origins, including the age of the earth and the cosmos. None of the offered explanations for these matters come without consequences for individual and social behavior, laying the ground for why people look at social policies as instantiating ethics and why then there’s such a clash of civilizations.

To help see how pervasive the need for simplicity and confirmation bias is, note that when people use the term “understand” as in “I want you to understand” or, often, when using the term "explanation," what is actually being asked for is agreement.

The modern world is such where “lived experience” is the ascendant method of truth-determination, and while that phrase is typically associated with those in progressive liberal groups, conservatives have their own versions in phrases like “I just know this to be true,” “it’s intuitively true,” “god says it and I believe it,” and “I still feel disrespected.” Regardless of the version, the goal is the supplanting of complexity and, therefore, the anxiety-inducing acknowledgment that one could be wrong with the simplicity of psychological fundamentalism.

Rationalizing Our Behavior

These tendencies in human psychology and social communication find rationalization in the use of Ockham's Razor (albeit not in a very nuanced form). Alternatively referred to as the "KISS (Keep It Simple Stupid) principle," the Razor is the favorite of anybody desiring to remove from consideration a particular conclusion of a contrary position. In other words, competing explanations are offered for a situation or entity, each having gone one step too far in the mind of the person holding the opposite claim. This situation is rather common in religious disputes, particularly in whether or not a claimed scientific appraisal is correct or the other person's god is needed. Both sides can and have utilized the Razor to claim that one or the other has "multiplied entities" beyond what is needed for an explanation, whether such refers to a god or to the complexity of an offered scientific theory.

Contrary to how his thinking has been used, Ockham himself was not concerned with simplicity. Consider this from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Ockham’s Razor, in the senses in which it can be found in Ockham himself, never allows us to deny putative entities; at best it allows us to refrain from positing them in the absence of known compelling reasons for doing so. In part, this is because human beings can never be sure they know what is and what is not “beyond necessity”; the necessities are not always clear to us.

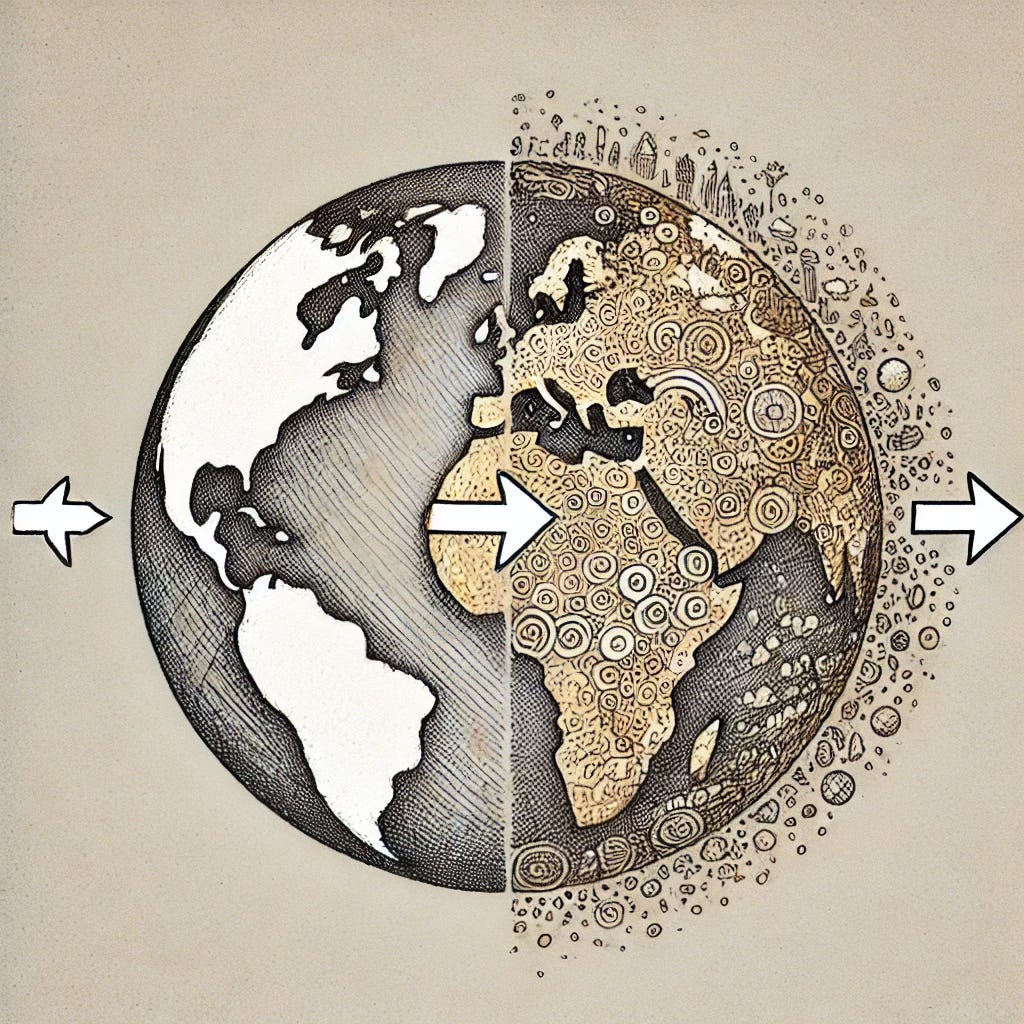

Rather than attempting to address skepticism concerning particular entities, Ockham was more concerned with noting the limitations of human knowledge. The difficulty of "beyond necessity" can be seen in a simple thought experiment. Pick an object in view and consider how it got there, perhaps a tree outside a window. Once selected, broaden the perspective out one step at a time, noting how things are connected. The tree needs a seed, soil, water, and sun, then the land itself and whether such was capable of sustaining a life of its kind, then how buildings and natural features constrained where it was possible to grow, the cityscape that those buildings are a part of, the societal structure the city is part of and onward into the cosmos. At what point is something considered a necessity? Which entity becomes superfluous to the explanation? Is there even one answer to these questions?

Focus, Not Simplicity

Precisely because of the interconnected reality of nature, necessity and parsimony will quite often be determined less by the context of the situation and more by the structure behind the inquiry. If asked to explain how a rock was thrown, physical mechanics may be brought up, but there's likely not much purpose in going into the geologic history of the rock itself. If asked, "Where did we come from?" the answer will be contingent upon just what is meant by "we" and the nature of what is meant by "coming from." With this in mind, a person's principle-driven worldview will determine the extent of a given explanation, what is considered sufficient, and when the simple is proclaimed to be needlessly complex.

Thus, it is that we come back to a consideration of what Ockham was most concerned with, determining the best explanations rather than the denial of things. The extent of the universe that is known continues to be astronomically smaller than that which is unknown. A simple explanation in the past has often been superseded by a more complex answer in the present and there is a high probability that it will be yet further replaced by or expanded into an even more complex answer in the future. If the first inclination when presented with a contrary explanation is to remove it in part or in whole then the concern isn't in expanding one's explanatory power, it's in expressing one's confirmation bias.

If there was a monument to ideas changed and cast aside throughout history, its base would be human hubris. The universe, even our individualized piece of it, is bigger than we cognitively grasp at any given moment, and that's a good thing.