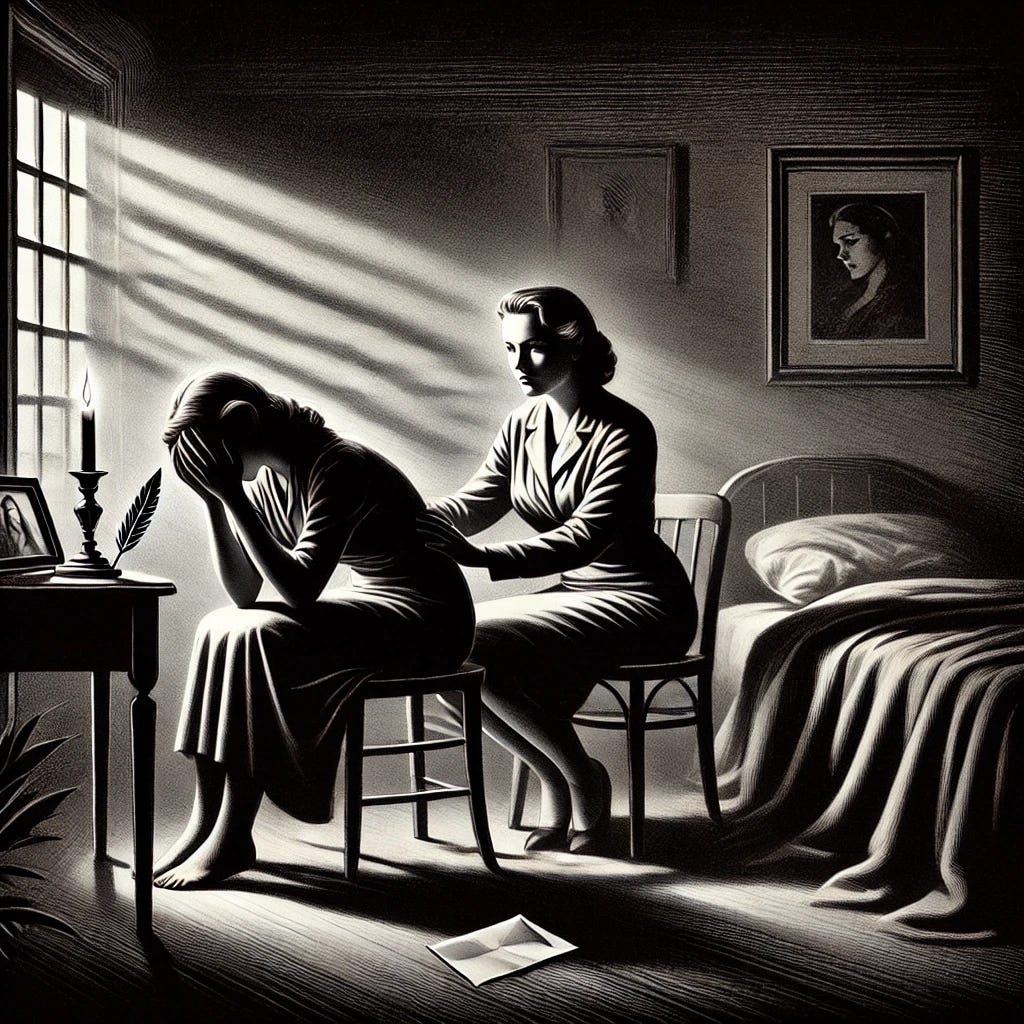

Being Present in the Space of Grief

How to Expand Empathy within a Shared Humanity

Grief, as much as it often inspires thoughts of separation, is our mind's way of recognizing how close we truly all are. Loss is as much a part of life as growth, each movement a step away from one space and towards another. There is no gender, economic status or race that is exempt. The form loss takes and the way each of us works through the consequences will differ, though never in such a way that it cannot be felt by someone else. Grief binds us together like strings connecting a human collage, disparate pieces being reminded they all exist on the same canvas.

Grief: A Foundation of Empathy

Separation and bonding, frustration and mirrored tears, the duality of grief can be bewildering. While we often think of empathy as an active creation to form social bonds, it is better understood as the conscious acknowledgement of bond that already exists. This is why imagination and varied life experiences is so important to the expansion of empathic living, the variability provides the creative space for acknowledging the shared humanity at the heart of every form of relationship.

One, albeit very technical, definition is provided by Preston and de Waal (2001):

"…any process where the attended perception of the object’s state generates a state in the subject that is more applicable to the object’s state or situation than to the subject’s own prior state or situation."

Don't worry if the wording is confusing as the attempt is being made to offer a general definition for multiple distinct processes in different contexts. Essentially, Preston and de Waal are noting that empathy is any process where one person (subject) views another being (object) as having a particular feeling or thought (state), such that what the person (subject) now feels or thinks is more in line with that of the other (object). In other words, empathy is a form of expansion of one's ego to include another.

The process has many forms, from the identity-melding of an infant with their mother to shedding tears when confronted with the suffering of another. Given the power of our imagination, and how other beings exist as story cut-outs in our mind’s eye, it’s no surprise then that we can create bonds and feel sorrow and happiness for characters in books and in film.

Of course, the degree of empathizing is not the same for everyone or for each situation.

"The more interrelated the subject and object, the more the subject will attend to the event, the more their similar representations will be activated, and the more likely a response. The more similar the representations of the subject and object, the easier it is to process the state of the object and generate an appropriate response." (Preston & de Waal, 2001)

To put it simply, empathy's degree of response will increase in direct proportion to:

How close the person feels themselves to the other person or situation

How similar the experience of the other is perceived to be to the person's own

If a person holds a worldview that separates themselves from others and has a shallow background of experiences, then empathy has little to build upon. Consider this from the starting place of imagination, where the broader one's vision of life is, the greater amount of available information there is for imagination to make connections that empathy can then use. This is one reason why we tend to feel a greater sense of loss for friends, family and loved ones than for strangers and why even those who we are close to will grieve over a loss that we find incomprehensible. No reaction on this scale is more or less human, more or less real, it is all a manifestation of empathy's continued processing of information.

Grief: Seeing the Pain, Seeking the Human

Grief is the acknowledgement of connection to someone or something that has been lost. It is the recognition that the future held in hope of being fulfilled, has been removed. However much pain is involved, the foundation is that of connection, of being able and having the opportunity to feel with more than yourself. Any uncertainty or confusion can be mitigated by reminding ourselves of this, that the loss is real and connection comes first.

"Supporting Someone In Grief" (O'Connor, 2006)

Listen attentively. Allow space for silence and reflection.

Don't use language that minimizes the loss or attempts to problem-solve

Remind the person there's no deadline for grieving; they can take all the time they need.

Provide practical as well as emotional support, months and years after the loss.

Encourage lots of rest, nourishing food and moderate physical activity.

Acknowledge anniversaries.

Allow each person his or her own grieving style; there is no 'right' way to do it.

Encourage use of community services if needed.

This list from O'Connor is fundamentally about using our skills of communication to encourage and build upon the process of empathy. By being flexible in our responses, we acknowledge the uniqueness of the other person's loss even as we seek to find something to connect to and help carry the burden.

Our ability to be present in with another's grief, to share the bond of humanity, is expanded or limited by the vision of our lives. Merely acknowledging that the way we see the world does not encompass all of it allows empathy to grow. Actively engaging in experiences that move the boundaries of our comfort allows empathy to expand. The extent of our humanity's expression is limited only by the depth to which we seek to explore it. When being present in the space of grief, we are taking part in a fundamental process of the universe, the cornerstone of the human spirit, that of interconnection.

References:

O'Connor, T. (2006). When grief is good. Intheblack, 76(8), 75-76. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/211289208?accountid=134574

Preston, S. D., & De Waal, F.,B.M. (2002). Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25(1), 1-20; discussion 20-71. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/212324365?accountid=134574

Further Reading:

Center for Creating a Culture of Empathy

Pomeroy, E. C. (2011). On grief and loss. Social Work, 56(2), 101-5. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/863249357?accountid=134574