"Who we are is a story of our self—a constructed narrative that our brain creates." (Hood, 2012) The how of that construction provides ample space for frustration when our actions don't fit what we believe ourselves to be; confusion when what we say is not as clear to others as it seems to be to us; and anxiety when confronted with terrible events and are unsure how to continue moving forward. Unfortunately the nature of self and how it is constructed is still a hotly debated topic with no clear winner, which means what is offered here is one opinion, though one with an eye towards helping some of the frustration and confusion diminish so we can meet adversity with greater clarity.

A Matter of Terms

To start, we need to look at a few ideas:

Self-Concept:

For most, this is a simple and rather painlessly easy task to answer, it's "me" or "I." Unfortunately that doesn't really answer anything, as such is simply replacing one term with another. What we're looking for is how the "I' or self-concept is structured, the means through which it is formed so differently as the billions of people on the planet. With that in mind we can look at what is offered by Showers and Zeigler-Hill (2007):

"A starting point of research on self-structure is the assumption that the self-concept is contextualized. That is, a person’s self-concept in reality consists of multiple selves, distinct identities that are represented by organized bodies of both declarative and episodic knowledge (Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987)."

Before getting too caught up in the verbiage, let's break it down. Essentially the self-concept or "I" is a mixture of different forms of knowledge brought together into cohesive wholes. To use the story analogy, consider the self-concept as a book, with the various selves as the chapters, each of which contains declarative (facts and statements) and episodic (perceived experiences and situations) knowledge.

Importantly the selves here are relatively coherent in themselves prior to exploring any links to the self-concept or "I." This is why we can have a "work-self," a "private-self," a "out-with-friends-self," etc. The social and environmental context provides a holding space in which a particular self feels safer or more authentic. Nobody expresses themselves in the exact same way in every situation. Again from Showers and Zeigler (2007):

"All models of specific structural features allow for contextualized multiple selves, and most imply that individuals define their own multiple contexts for their identities. That is, the contextualized self is actively constructed by individuals who shape their own self-categories and contexts as part of their general motivation to make sense of the world and to function adaptively within it (Heider, 1946; Kelly, 1955; Mischel & Morf, 2003). Thus, contextualized identities may correspond to some combination of internal states (‘‘me when I’m happy’’), external environments (‘‘me at work’’), roles or relationships (‘‘me as a friend’’), or experiences (‘‘success’’)."

Authenticity is not about being the same all the time, but whether the variations in our behavior link to a broader pattern. In other words, can a person who knows you come to expect a particular set of actions when within a new situation based on what you have done before? There is certainly room here for the problems of assumptions and the common problem of thinking we know more about another person than we actually do, but essentially the charge of "hypocrite" is a declaration of "based on what I've seen before, you should be acting this way but aren't." We consider ourselves to be the same person not because there's only one self, in this usage of the term, but because each self interrelates with all the others to varying degrees. How those selves connect is where we turn now.

Compartmentalized and Integrative:

The multiple selves of the "I" can be brought together in two general ways: compartmentally and integrative.

Compartmentalization is about keeping selves as separate as possible. In staying with the story analogy, it would be like chapters being removed and given to a reader in no particular order and with little hope for getting the whole. There remains the potential for links to be found, but it's difficult to do so, particularly if the contexts are widely separated.

Integrative structuring is about actively holding multiple selves with a focus on their linkages. This does not mean becoming a single self, rather it's about dwelling on the similarities within the differences. Another way of putting it is noting the basic Values that a person holds, even as they manifest in different ways for each self as it moves within a particular context. A person can hold to the Value of honesty, but that doesn't mean they're going to share every intimate moment of their partner with people at work or express all a company's inner-workings at home.

Finding Mental Health within Self-Concept

The process of a self-concept being formed is a constant journey of taking in new information, revision, and an exploration of whether any new self will allow one's expression in a particular context with as much authenticity as possible. However, any knee-jerk responses should be curtailed immediately. While it may be easy to see where compartmentalization can lead to greater degrees of hypocrisy, both it and integration are tools, not systems connected to a black-and-white judgment.

Consider a person who's job is difficult in an emotionally draining way or if it is perceived that a particular situation calls for a shifting of one's Values for expression, perhaps where honesty is suborned to personal safety. Compartmentalizing is, in these situations, greatly helpful. Calling out hypocrisy is to ignore the demands being placed on the person. There are, however, consequences to using this tool.

"...for individuals with relatively compartmentalized self-structures, daily self-esteem reports fluctuated with the number of positive and negative life events occurring on that day. Moreover, compartmentalized individuals’ self-esteem was especially sensitive to a laboratory manipulation of social acceptance or rejection. In other words, compartmentalized individuals seemed vulnerable to dramatic shifts in self-evaluations in response to daily events." (Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007)

Notice that the vulnerability is related to the person's connection with social relationships. Because the person's various selves are more disparate or disconnected, there is a greater degree of instability when faced with adversity outside of the original context that called for compartmentalizing. As a behavioral example, the need for expressing more control in one's personal life may be an attempt at mitigating the stressors outside of their separated work life.

None of this lets integration off the hook for potential consequences.

"Studies of structural self-change are consistent with the view that greater integration may often reflect an ongoing struggle to resolve negative self- or partner beliefs. This struggle may or may not be successful in the long run. Our findings suggest that it is most likely to be successful when the structure is positively integrated or when stress or conflict is low." (Showers & Zeigler-Hill, 2007)

Integration is not an easy tool to use. By deliberately attempting to bring disparate chapters together to create a coherent book, it's often like being handed them one at a time and without either headings or chapter numbers. As in the compartmentalizing behavior example, control may be utilized as a means of lowering stressors in order to diminish the perceived conflict between multiple selves.

Certain ideologies may be considered helpful in working with either of the tools available. A belief in an ordered world of black-and-white judgment can provide the grounds for finding comfort when faced with the feeling that a self is too different from what the world seemingly asks to see. For that matter, the inner conflict of working through integration can be salved through a belief in the need for a higher purpose, in any form, providing a way to link certain parts and leave others alone.

"Campbell et al. (1996) define self-concept clarity as the extent to which the contents of the self-concept are clearly and confidently defined, internally consistent, and temporally stable." (Campbell, Assanand, & Paula, 2003) The difficulty here is that internal consistency and confidence do not immediately translate to health or any social good. The contents of any self-concept are self-servingly selected by the person in question.

What may need to be kept in mind is that the formation of a self-concept or personal story is a constantly evolving one. What to be wary of is whether one has stopped asking questions. Where stagnation emerges, growth has stopped. Integration may indeed be linked with a greater degree of psychological well-being, but integration is a tool for residing in an on-going struggle for internal cohesion. Such a journey is one that never ends, even as there can be found a degree of comfort in the exploration.

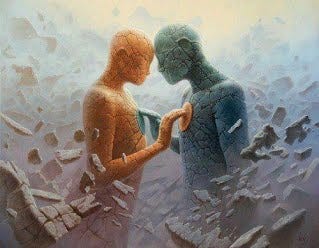

Featured Art by Elreviae

References:

Campbell, J. D., Assanand, S., & Paula, A. D. (2003). The structure of the self-concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71(1), 115–140. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.t01-1-00002

Hood, B. M. (2012). The Self Illusion: How the Social Brain Creates Identity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Showers, C. J., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2007). Compartmentalization and integration: The evaluative organization of Contextualized selves. Journal of Personality, 75(6), 1181–1204. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00472.x

Further Reading:

Alatiq, Y., Crane, C., Williams, J. M. G., & Goodwin, G. M. (2010). Self-organization in Bipolar disorder: Replication of Compartmentalization and self-complexity. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(5), 479–486. doi:10.1007/s10608-010-9315-1

Turner, J. E., Goodin, J. B., & Lokey, C. (2012). Exploring the roles of emotions, motivations, self-efficacy, and secondary control followin